The Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW)

A landmark social change

One of the most successful advocacy efforts on behalf of women in the 20th century was the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) through the 1980s and 1990s. Its aim of the priesting of women was achieved in 1992. Since then women have gone on to become bishops and archbishops. However, the struggle is not over in some dioceses, notably Sydney.

Lambeth Bishop’s Conference 1988: A Bevy of Bishops, a Pride of Protesters

MOW Australia at Bishops’ Lambeth Conference in Canterbury. Street march in London, St Pauls Cathedral, 1988, advocating for the ordination of women in Australia.

Click for more

In 1988 some countries had been ordaining women priests, but the Australian Synod in 1987, by a narrow majority, had voted against women priests. So, six Australian women from the Movement of the Ordination of Women took their position on the international scene by journeying to Canterbury, camping on the Canterbury Plains in a caravan and tent, in the freezing cold. At this conference, presided by Robert Runcie, then Archbishop of Canterbury one of the matters to be debated was the consecration of women as Bishops. According to Alison Cotes who was there, “we begged and borrowed from friends and supporters to fund us for this trip”. In their different ways they made the journey to Kent to set up shop in a caravan on the Canterbury Plain and camped in an uncomfortable tent. Their public relations person, Diane Heath, tapped away on a typewriter to send their messages back to Australia by fax machines.

As the Bishops processed into Canterbury Cathedral, they persuaded the police to give them the front row where they displayed a home-made banner on an old linen sheet that said, “Australian Women for Ordination’, linked with the Australian flag. The Archbishop of Canterbury came over to welcome them. They invited Bishops to their parties; a few Bishops came but the Australian Bishops would not talk to them. In fact, Alison received a letter from her Bishop who told her “This is none of your business, you shouldn’t be here; women’s ordination is the business of the Bishops”.

The final Bishop’s event was a service at St Paul’s Cathedral where, joining with a few Australian women, thousands of people marched around the Cathedral. Again, they carried one of their banners, “Let the Bishops listen’. They were ignored by the Australian Bishops, but kissed by Bishop Desmond Tutu, and shook hands with Richard Holloway. Their conclusion was that their presence made a difference.

Alison Cotes

Philippa Wetherell (1938–)

From opponent to priest

Click for More

Philippa Wetherell (1938–)

Philippa Wetherell went on a journey from opposing the ordination of women to becoming a priest herself. As a young woman in the 1960s, she joined the Society of the Sacred Advent, an Anglican religious order for women. After 25 years she left the order to be a pastoral carer, university student and a priest.

Philippa Wetherell, better known as Pip, has led a life characterised by change. Firstly, in her attitudes towards the priesting of women – from the 60’s where she thought that God only called men to the priesthood; to the 80’s where she saw the exclusion of women priests as a justice issue, but not for herself; to 2003 when she was priested at age 65. Secondly, after serving as a nun in the Sisters of the Sacred Advent for 25 years, from a very young age, she stepped out of that role to a place of growth and learning, which led her to a change of location from the place where she had grown up, Brisbane, to Melbourne.

Pip was born in Brisbane in 1938 and grew up in the Parish of Sandgate, and from the age of four attended Sunday School at St Nicholas Shorncliffe Church of England. Confirmation at age twelve was very special for Pip and receiving the sacrament was very important for her. Meeting with the first Anglican Sisters, while she was at Grammar School, was significant for Pip. It was in 1957, at age 19, she felt that God was calling her to Religious Life.

When she told her parents, her poor Mother was totally dismayed that she planned that, as soon as she was 21, she was going to test her Vocation as a Sister of the Sacred Advent (SSA)! She who had nurtured her faith, now tried to stifle it. The whole idea of being a nun was anathema to her Father who wanted to disown her. Still she joined the SSA and persevered.

In January 1960, at barely 20, she went to live at the Community House at Albion Heights. Life in the Novitiate was certainly a challenge, but she was clothed in the Habit in August and continued teaching in the Primary School at St Margaret’s. In the sixties she taught at four different SSA schools and made her profession in 1963. Amazingly her Father shocked and delighted her by turning up in his best suit!

In the 60’s she thought that God only called men to priesthood but in the 70’s she began to think differently about a number of things in the Church. Beginning a degree at James Cook University in Townsville opened her eyes to many new understandings. She sought permission to attend a weekend conference at which she heard Monica Furlong speak and listened to the ideas of a group of Brisbane women who were working towards ordination being open to women, the beginning of the Brisbane Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW). She was convinced this was a justice issue, and discriminated against women, but was not for her personally.

In 1985, while she was a Chaplain at University of Queensland, she felt God was calling her out of the Community of which she had been a part for 25 years. Even though the vows she had taken were precious, she felt she could not grow as a person and indeed, as a woman, within the conservative ethos of SSA and under the leadership of an authoritative Mother Superior. This momentous and courageous step led her to move away from Brisbane, her home town. She accepted a bursary to do pastoral work at the Brotherhood of St Laurence, Melbourne, and did a course in Clinical Pastoral Education. This showed her the rightness of her decision.

She played an active part in the struggle towards the priesting of women, but wasn’t sure if it was for her. She was overwhelmed by the vast Diocese of Melbourne and feared she would not be accepted as a candidate for ordination. So she went off to Papua New Guinea in 1994 as an Australian Volunteer and did the Bachelor of Theology at the Uniting Faculty of Theology. In 2001, after four years at Newton Theology College in Popondetta, her friend, Lesley McLean, priest and current President of MOW, lured her to Eyre Peninsula, South Australia where she spent 8 years in ministry. In 2003 in the diocese of Willochra, she became first a deacon, and then a priest at age 65.

Janet Scarfe (1947-)

MOW luminary

Click for More

Janet Scarfe (1947-)

Janet Scarfe was the second President of the national MOW and served from 1989 to 1995. The secretariat of MOW moved from Sydney to Melbourne, a diocese more committed to the ordination of women. Janet was present at the General Synod of 1992 when the ordination of women as priests was passed. She is a believer in wit not lamentation or polemic.

For many people the names ‘Movement for the Ordination of Women’ and ‘Patricia Brennan’ were and still remain synonymous. MOW and its public persona were infused with Patricia’s vision, energy, incisiveness and personality during her presidency and beyond.

That in itself meant following her as president in 1989 was a daunting prospect. The context made it even more so. In the months following my election, General Synod again rejected the ordination of women as priests, champions of women’s ordination Archbishop David Penman and the Reverend John Gaden both died, and the Appellate Tribunal raised further obstacles. ‘Pro’ bishops who had voiced their support for action froze.

The next General Synod vote was not due until 1992 – an eternity away. MOW had to keep busy, constructive and visible in the meantime.

The MOW secretariat moved from Sydney to Melbourne, an Anglican environment that was committed to the ordination of women, albeit with provisos. MOW Melbourne was a large and active branch, and very supportive of its members with a national role.

As I understood it, the MOW president had various functions. Honouring the past was one and so the National Network formally recognised Patricia as founding president, published a festschrift of essays and successfully nominated her for an Order of Australia. It was a privilege to prepare the nomination and be present at the ceremony.

Another role was to build credibility with women who had been ordained deacon (at least 125 by 1991). A prayer diary for women clergy became a means of communication and provided a reason for me to write to them every year. (Obsessively) I tracked ordinations and appointments and so could provide accurate figures on demand to the media and to the Church itself which invariably seemed to under-estimate their numbers. Clearly women deacons were running parishes, preaching sermons, conducting services and providing pastoral care – doing everything a priest did except preside at the eucharist. New software (c1990) on my office computer resulted in the ‘Deacons Density Map’ used widely (though not all liked the title!).

MOW National’s reputation as a source of credible information grew. I compiled ‘Ebb and Flow’, sent regularly to the branches with information, news and an ‘Inverted Mitre of the Month’ award for recent sexist comments by church leaders (never hard to find). Wit seemed to me better than lamentation or polemic. Before the crucial General Synod of July 1992, MOW National’s information pack for each synod member included an apparently light-hearted quiz I wrote challenging misinformation and misconceptions in the debate in Australia and elsewhere. (Q: How many ordained women are there presently in the Anglican Church of Australia? A: 12 priests and 160 deacons.) I was delighted and humbled to be a member of that synod after a Melbourne ‘anti’ could not attend.

The Australian newspaper described MOW as ‘one of Australia’s most forceful reform movements’ (30 September 1992, p9). The creative work and commitment of many besides the two presidents made it so – in branches and parishes, in hymns and prayers, in demonstrations and research.

After I left MOW in 1995, I drove around Australia interviewing/conversing with over 260 of the first generation of women deacons and priests. The precious recordings and transcripts (1.4million words!) are now in the State Library of South Australia. Later I co-edited with Elaine Lindsay and contributed to essays to mark the 20th anniversary of women priests, ‘Preachers Prophets and Heretics’ (NewSouth, 2012).

Sometimes it all seems like only yesterday.

Janet Scarfe

National President, MOW 1989-1995

Gwenneth Roberts (1937-)

MOW pioneer, social justice activist

Click for More

Gwenneth Roberts (1937-)

Inspired by Patricia Brennan and Monica Furlong, Gwenneth Roberts initiated the Brisbane Movement for the Ordination of Women. She is a committed social justice campaigner.

Gwenneth Roberts is one of the pioneers of the Movement for the Ordination (MOW) in Australia. She initiated the Brisbane branch, one of the first in the country, and attended the historic meeting in Adelaide in 1984 at which the movement’s national network was formed.

Gwenneth’s commitment to MOW came after a serendipitous encounter with Dr Patricia Brennan. Patricia was a doctor, former missionary and outspoken campaigner against the discriminatory treatment of women in the Diocese of Sydney and particularly their exclusion from ministry as deacons, priests and bishops. She had formed an organisation in Sydney called the Movement for the Ordination of Women to fight that exclusion.

Inspired and encouraged by Patricia, Gwenneth set up MOW in Brisbane and became co-convenor with Marian Free (subsequently the Rev’d Canon Dr), and later Dr Mavis Rose. From the beginning she gathered together members into an active committed branch. They hosted a visit of the MOW (UK) convenor Monica Furlong in 1984, held intense discussions on the nature of priesthood, ran retreats for its members, wrote their own inclusive liturgies and issued publications.

Gwenneth’s was a deeply committed albeit questioning Anglican, and represented her parish in Diocesan Synod for a number of years. At the same time, she worked tirelessly with Brisbane MOW and the National Network so that the Anglican Church would eventually recognise that God does indeed call women to ordination, leadership and visibility in its structures.

Gwenneth juggled her commitment to MOW with her personal and professional life. She and her husband John, a gastroenterologist, had six children. She was a qualified and experienced nurse, midwife and childhood educator. She worked in the late 1980s as an epidemiologist in the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program at Queensland Health, during which time she herself was diagnosed with breast cancer. She was an advocate of breast screening programs (not universal in those times) and worked in post-cancer exercise and information programs.

Gwenneth added university studies to her responsibilities. Her field of academic expertise was domestic and family violence. Her doctoral research – the presentation of victims of domestic and family violence in the emergency department of a major public hospital – was groundbreaking. She developed a particular interest in the hidden violence in the Anglican, Catholic and Uniting Churches, working with Queensland Churches Together in the 1990s.

Gwenneth’s determination to assist the voiceless and excluded be heard was all pervasive. For decades she has been involved with First Nations communities in Brisbane, standing with elders Auntie Jean Phillips and the Rev Alex Gater on their journeys. She has organised home groups to educate the non-indigenous community and supported organisations addressing the ongoing effects of colonisation and oppression on First Nations people in Australia.

In recent times, Gwenneth has become an active member of St John’s Cathedral Community in Brisbane. She has rejoiced in the commitment to social justice for the excluded and voiceless among the clergy and people there.

Joan Lethlean (1942 – )

MOW member, activist

Click for More

Joan Lethlean (1942 – )

Joan Lethlean compares her experience of the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) to that of her uncle, Bishop Ronald Hall who ordained the first Anglican woman priest, Florence Li Tim-Oi in 1944. Both faced the disapproval of many.

In Joan Lethlean’s story she makes a comparison between herself and her Uncle, a Bishop, both of whom did something which met with disapproval. This is Joan’s story, and these are her words.

“When I was a little girl in England, my uncle, Bishop Ronald Hall came to visit. Somehow I picked up the message that he had done something that people disapproved of. It was many years later that I learned that Bishop Ronald Hall, Bishop of Southern China and Hong Kong, was the first person in the Anglican Church to ordain a woman as a priest. During WWII, faced with the lack of clergy, he arranged to meet Florence Li Tim Oi behind the Japanese lines and, after a night of prayer, ordained her as a priest. (Based in Macau, Li Tim Oi had built up a thriving ministry.) When the news of Bishop Hall’s action broke, there was instant disapproval back home in England.

Many decades later I was faced with related disapproval as a member of the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW). The thought of women priests brought forth deep emotions on both sides of the debate. Thus it was that I responded with mixed emotions to an invitation to a live-in weekend welcoming Monica Furlong from MOW England. As it was being held at the Catholic Augustinian priory I assumed that I would not know anybody and would be safe among Catholics in my anonymity! Imagine my surprise when I knew lots of people, as it was an Anglican event. As people shared their stories over the weekend we gathered enough courage to form a branch of MOW here in Brisbane.

Being a member of MOW gave me courage to speak at synod and to take part in many demonstrations outside cathedrals and churches. Annual MOW conferences helped us to bring humour into our struggle as, with some irony, when we acted out all the reasons why men should not be ordained. As I took part in debates I found myself challenging the argument that women could not represent Jesus at the altar.

Now that many women have been ordained we need to remember the struggle we went through to make sure that the debate took place. As my uncle Bishop Ronald Hall found out, it did not happen without the disapproval of many”.

Elaine Lindsay (1948 – )

Activist, academic and journal editor

Click for More

Elaine Lindsay (1948 – )

Elaine Lindsay has been actively involved in feminist theology and spirituality since the late 1980s as an activist, academic and journal editor. She has been most closely associated with the Movement for the Ordination (MOW) and with Women-Church, An Australian Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. She is a firm believer in the ministries of witness and irritation. Elaine challenges the theological position of headship widely held by the Sydney Anglican Diocese.

“My closest friend, dating back to our first day at St Peter’s Collegiate Girls’ School in Adelaide is Janet Scarfe. It was Janet, a foundation member of MOW in Melbourne, who introduced me to the charismatic Patricia Brennan at the 1987 Sydney launch of Opening the Cage: Stories of Church and Gender (eds Margaret Ann Franklin & Ruth Sturmey Jones). I was ripe for activism and MOW, having experienced a celebration of the Eucharist by a woman-priest at the cavernous Cathedral Church of St John Divine in New York in 1986. It showed me that women had a place at the table, could pierce the patriarchal darkness, and bring a new understanding to a familiar liturgy. Since the late 1980s I’ve been a member of MOW, sometimes on the committee, and sometimes not. I’m culturally Anglo-Catholic but, by disposition, non-sectarian. My MA in Religious Studies at the University of Sydney (1991) reinforced my belief that all religions are shaped by the cultures out of which they grow and that one cultural expression isn’t superior to all others. I’m drawn to the writings of the mystics, where the Divine is experienced, not codified – indeed, this was the basis of my PhD thesis, Rewriting God: Spirituality in Contemporary Australian Women’s Fiction (Editions Rodopi, 2000). Rewriting God was a search for an Australian spirituality, drawn from women’s memoirs and fictions and hitherto unrecognised by male theologians.

Between 1992-2007 I co-edited Women-Church: An Australian Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion with Camille Paul. The journal was unique in that it was non-denominational, ran academic articles and reviews alongside poetry and memoirs and coverage of significant events, and was enlivened by the satirical drawings of Graham English. It’s been digitised by the University of Divinity so the work of its 280+ contributors will continue as an historical record of Australian women’s spirituality and struggles with religious authority. As an inveterate networker, I’m a sucker for conferences, conference committees, and editing conference proceedings. Since the late 1980s I’ve been involved with most of the MOW national conferences (gatherings painful, healing and hilarious) and national ecumenical feminist theological conferences.

After the first ordinations of Australian Anglican women to the priesthood in 1992, many of us thought the battle was almost won; we did not count on the intransigence of the Diocese of Sydney and several smaller Australian dioceses. Sydney may not have invented the doctrine of complementarianism, but it underpins its idea of headship where the male is head and female is subservient, whether in church or in the home. This seems to be justified by a peculiar (heretical?) interpretation of the Trinity, whereby the Son is eternally subservient to the Father. Sydney MOW does not have the resources to overcome this theological intransigence. As I see it, the best we can do is to maintain a ministry of irritation, a continuing thorn in the side of the diocese, and a support for those who believe ‘there is neither male nor female’ for we are ‘all one in Christ Jesus’ (Galatians 3:28). MOW National, by maintaining a ministry of witness, can warn those Australian dioceses where Sydney is spreading its heresies. But public interest in church doings has waned, tertiary studies in feminist theology have withered away and feminist theology organisations are scarce as hens’ teeth: the western world has moved on to more urgent issues.

We are aging, our legacy is in our history (recorded in Preachers, Prophets and Heretics: Anglican Women’s Ministry, 2012, conceived of by Janet Scarfe and edited by Janet and me), but we have not achieved the transformation of the Anglican Church throughout Australia. Nevertheless, we persist: MOW National is organising a national celebration of 30 years of Australian women’s priesting for September 2022 with the working title, ‘Unfinished Business’. It will, of course, be held in Sydney.”

The Reverend Dr Elizabeth J Smith AM

Priest, author, liturgical theologian and veteran of MOW

Click for More

The Reverend Dr Elizabeth J Smith AM

Elizabeth Smith AM is a priest, author, liturgical theologian and veteran of MOW in the 1980s. Many MOW members wore protest badges she created, and sang hymns and prayed using texts Elizabeth wrote. Some of her inclusive language texts are in the Australian Hymn Book 2, “Together in Song,” and her Australian-accented prayers are in wide use.

I grew up in a strongly Christian household. We five Smith children attended Church of Christ Sunday School every week, as well as morning and evening church services. When I was 10, I chose to be baptised, and enjoyed the pre-baptism classes with fascinating glimpses of critical biblical studies that I would not see again until I started a theology degree in the 1980s.

With family moves, we worshipped with Presbyterians, who became Uniting Church, until in my University years I started going to Anglican services on campus. I was struck by the simplicity, brevity and accessibility of the 1970s draft liturgies for the A Prayer Book for Australia. Thus began my ongoing relationship with the Anglican Church and its evolving liturgical tradition.

While teaching in state secondary schools, I studied theology in the evenings at the United Faculty of Theology. I met fellow Anglican students from Trinity College, mostly men, but also some women hoping for ordination.

Alongside the excitement of theological study, I got involved in 1980s Anglican politics, debating women’s ordination. The people and conferences of MOW (Movement for the Ordination of Women) were formative. There was energy, creativity, deep prayer in MOW, and many vibrant women and committed men putting their theological convictions into practice. My own creative streak was encouraged as I made badges both satirical (“I’m just a simple, bible-believing Christian feminist”) and theological (“Women priests have real presence”). I began writing prayers and hymn texts in inclusive, expansive language, beyond the “men and brothers” and the male names and prounouns for God that were everywhere in official resources.

After many people urged me to consider ordination, I offered, and was eventually accepted for ordination as a deaconess. By 1987, when I had finished my degree and a full year of Clinical Pastoral Education, it was possible for me to be ordained as a deacon. I served a curacy in Altona and another in Mount Waverley, in congregations and with senior clergy very supportive of women’s ordination. Some of the inclusive-language hymns I had written gained considerable popularity, around the Anglican Church and beyond. I received so many requests for copies that the Mount Waverley parish published them in two small books, so they could be widely sung. People wanted words that did not sideline women, because (as another badge declared) “God is not a boy’s name.”

By 1991 it was still not possible for women to be ordained as priests, so I chose doctoral study at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California. I had four good years in the Episcopal Church, in the seminary chapel at the Church Divinity School of the Pacific and at Good Shepherd Church in Berkeley, writing many more hymn texts and prayer texts. My PhD explored what a good thing it would be for Anglican liturgy, if we took seriously the insights of feminist biblical hermeneutics. In 1993, on a short visit back to Melbourne, I was ordained as a priest.

Back in Melbourne in 1995, I began what became 13 years at St John’s Bentleigh, a middle-suburban parish whose immersion font allowed me to recapture some of the insights of my Church of Christ formation. I put my feminist theological principles into practice, with some good results, and some resistance.

I was appointed to the General Synod Liturgy Commission, and in 2021 am still a member. In recent years, I have written fewer hymn texts. But many of my prayer texts, after a decent polishing by the Liturgy Commission, became part of the extended resources available to Australian Anglicans via Commission’s page on the General Synod website.

In 2008 I moved to Perth, into a diocesan role, training lay people and clergy for the diocesan mission plan. In 2015, I moved to the parish of The Goldfields as “mission priest.” In 2021 I am still in Kalgoorlie, improvising on what Anglican life, faith and liturgy may be in a society now thoroughly post-religious. My most recent hymn text, “Nothing less than love has saved us,” was written for the installation of the Most Reverend Kay Goldsworthy as Archbishop of Perth in 2018. And I still have the badge-making machine!

Rev’d Dr Alison Cheek

“Bishop to Australian women”

Click for More

Rev’d Dr Alison Cheek

In 1974 the Rev’d Dr Alison Cheek was one of the Philadelphia Eleven, the first women ordained in the USA, ‘illegally’, two years before official authorization by the General Convention. Born in Adelaide, but later resident in the USA, she became a significant figure and encouraged women by visiting Australia, including Brisbane, in the early days of the Movement for the Ordination of Women. A woman of stature and faith, she was given the symbolic designation as their ‘Bishop’.

Alison visited at critical times such as 1987 and 1989 General Synods where the canon to pass women’s ordination failed, giving sympathy and encouragement when women’s ordination was slow to progress. She was a close friend to many in MOW.

Alison left the USA in anticipation of a joyful celebration of women priests in Goulburn Diocese in February 1992. Between her departure and arrival an injunction was served on Bishop Dowling from Sydney Diocese to stop the planned ordination of women in that Diocese. This made Alison’s presence even more critical as she was able to spend time with the women deacons at their retreat the night before the planned ordinations, as well as with MOW members who were distressed by the outcome.

Alison was born near Adelaide in 1927, and graduated from the University of Adelaide in 1947. She moved with her husband, Bruce, to Washington, USA in 1957. With four young children at home, she was active as a lay leader in her local Episcopalian Church and became one of the first two women to enter the Bachelor of Divinity course at Virginia Theological Seminary. It was here she heard the voice of God, ‘I want you to be my priest. It was so powerful and that’s why I never thought of giving up’.

On graduation she commenced training and working with the Washington Institute for Pastoral Psychotherapy. She was ordained the first woman deacon in the South in 1972. When the opportunity for the Philadelphia ordination came in 1974, she thought, ‘Well, if they toss me out, at least I’ll go witnessing to what I believe about the Gospel and about women’s appropriateness for being priests, and being true to what I believed’. In Washington she became the first woman to celebrate the Eucharist in an Episcopal Church, in defiance of the diocesan Bishop.

Alison became active in marginalized groups such as the gay movement, black movement, and women in poverty, sticking to the margins of the Church to exercise her ministry. In 1976 Time magazine named her as one of 12 Women of the Year for her advocacy and action on behalf of women’s ordination. She later served at the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she was hired as Director of Feminist Liberation Studies and earned her Doctor of Ministry degree in 1990.

In 1996 she joined the Greenfire Community and Retreat Centre in Tenants Harbor, Maine, where she served as a facilitator, teacher, and counsellor.

A friend said of Alison, ‘Her abiding sense of joy, her obvious intelligence, and deep passion for the Gospel of Jesus, combined with a delightful touch of mischief in her eye made her an irresistible and unforgettable presence. When her story is told, it will be said that we once walked among giants’.

Alison died in 2019 at her home in North Carolina.

Mavis Rose (1927–2019)

Author, MOW activist and black sheep

Click for More

Mavis Rose (1927–2019)

Self confessed Anglican guerrilla, Mavis Rose was a prolific letter writer to the Anglican church advocating for the ordination of women. She saw ordination as a step on the way to freeing the church from a culture of devaluing women. Her PhD thesis was entitled ‘Freedom from Sanctified Sexism: Women transforming the church’.

Mavis Rose, an activist and leader of the Movement for the Ordination of Brisbane wrote that she came to think of herself as an Anglican guerrilla. I may not use bombs, but I believe it is the prophetic role to bombard decayed, patriarchal structures. So Mavis engaged in speaking out, and prolific letter writing to the Anglican Church and secular press about women’s oppression in the Church. These activities earned Mavis the unenviable title of “the black sheep of the Anglican church.” After her death she was hailed as a “hero of the Diocese”. She said that she was once very square and conservative but a simple incident changed her.

The late Dr Mavis Rose was born in Bray, Eire, in 1927, and baptised into the (Anglican) Church of Ireland. She came to Australia in 1951. As secretary to the Personnel Manager of TAA she met an aeronautical engineer, Calvin Rose , whom she married in Melbourne in 1953. They moved to Kampala, Uganda for Calvin’s appointment at Makerere University. Between the birth of three daughters, Mavis fulfilled significant positions with Kampala Municipal Council, and set up the first Girl Guide Troop in Uganda for which country she became the Guide Commissioner.

In 1973 they moved to Brisbane where Mavis was able to take up a long-held ambition to commence University studies. Mavis completed BA (Hons) and MPhil in the School of Modern Asian Studies at Griffith University, where she later taught Indonesian Language, an activity aided by significant periods of residence in Indonesia researching for a political biography of Mohammad Hatta. Her biography was published by Cornell University Press, and she translated this into an Indonesian language book following requests from that country.

Mavis had a life-long association with the Anglican Church, but said that her journey with the Movement for the Ordination of Women (or MOW) began at a weekend gathering in Brisbane with the UK leader of MOW, Monica Furlong which included many women who had experienced a vocation to priestly ministry. With tears in their eyes, they spoke of their deep sorrow when their hopes for ordination had been denied by the structures of the Church. Mavis sensed that she had to do something about raising the consciousness of women about this situation, which she saw as demeaning.

The simple incident that galvanised Mavis into her activism was the cancellation of a dinner to welcome an overseas visiting woman priest, to be held in her local Church, by the Rector, five days before the event.

Mavis challenged male headship with banners and demonstrations outside St John’s Cathedral in Brisbane, and engaged in prolific letter writing. Letters and verbal abuse soon followed from all quarters, describing MOW members as “witches on the way to hell”. Such opposition strengthened the determination of Mavis -and MOW members (I quote from her diary)- “to free the Church of such domination and consequent devaluation of women”.

In 1989 when progress to women’s ordination was slow Mavis’ words encouraged and emboldened Anglican women. She said “we have to renew our courage and start to act more boldly, remaining assured that the Holy Spirit is with us. We are faced with further injustice – but God is Perfect Justice and we are confident of God’s strength and protection. We have women in our Diocese whose spiritual calibre is such that we believe they should be able to fulfil their vocation”.

Mavis completed a PhD in Religious Studies at the University of Queensland, The resulting thesis was published with the interesting title: “Freedom from Sanctified Sexism: Women Transforming the Church”.

Mavis was a respected academic but she also had a ‘grass-roots’ ministry to women. She could reach out to women who were experiencing great difficulties in the Church with imaginative compassion.

The ordination of women was, for Mavis, a staging post – a start on a process. She saw that whilst the ordination of women was a necessary beginning, a much wider struggle remains to deal with the social and organisational structures of the Church, its ancient language and theological weaknesses, and its commonly limited ability to contribute to the main issues raised by the messages of Jesus such as justice, openness and love.

In 2011 Mavis wrote a book entitled “Gender Balanced Belief- A New Ethic for Christianity” which will be published posthumously in 2021, following her death in September 2019. This book greatly expands her previous analysis of the role of sexism to now cover all churches, including those with centrally patriarchal structures, and those churches outside the mainstream. The core assumption of the book is that the sexist distortion that has developed in Christianity is redeemable, and that Jesus of Nazareth provides a relevant and vibrant role model for today’s world. The book ends with a realistic review of the historical, social, cultural and power-based hurdles that would continue to inhibit the gender-just reformation already underway in some sections of the Christian Church.

Alison Cotes (1940 –)

Educator, foundational member of MOW

Click for More

Alison Cotes (1940 –)

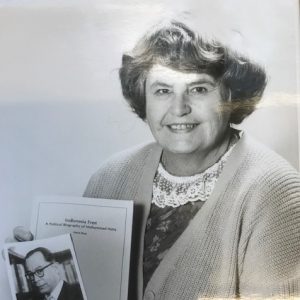

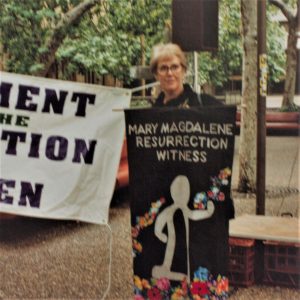

An expert on Mary Magdalene, Alison Cotes met Patricia Brennan in and became a foundational member of the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW). She is now agnostic and is working on Judas Iscariot who, like Mary Magdalene, was a misunderstood outsider.

Alison Cotes has filled a myriad of roles in her fascinating and fulfilling life. She is a grandmother, academic, journalist, former Manager of Queensland Performing Arts Centre, theologian, radio broadcaster and playwright.

After teaching on the Kokoda Trail in Papua New Guinea for seven years, Alison Cotes moved to the University of Queensland where she taught in the English Department for fifteen years and began her PhD studies on Mary Magdalene in myth and literature. It was during this period that she became passionately interested in feminist theology, met Patricia Brennan and became one of the foundational members of the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW). She enjoyed it because it was inspiring, took initiative, was not dull, in fact a lot of fun.

Alison considers herself an argumentative person, and she happily engaged in debate with opponents of women’s ordination. Interestingly she had friends who were on both sides of the debate. She names Canon James Warner, a friend, who publicly was a great supporter of women’s ordination. She also had friends who were vehemently opposed to the issue. Alison’s tradition was Anglo-Catholic and it was from this area that strong opposition came. She names one as All Saints’ Anglican Church, Brisbane. However, she managed to speak from the pulpit there, and became a regular preacher.

Alison was part of a six-member unofficial delegation to the Lambeth Conference, Canterbury, UK in 1988. They camped in an uncomfortable tent; entertained Bishops; terrified the Australian Anglican Primate, who refused to speak to them; drank too much Australian red; marched on the Bishop’s meeting at Westminster Abbey; got kissed by Desmond Tutu; generally had a ball; and made a difference.

Alison developed a great interest in the Magdalen figures of the late Victorian era who were presented as prostitutes. This led her to explore Mary Magdalen’s story and to discover that she was not a prostitute, but a foremost apostle, close to Jesus, and had been misrepresented throughout history. Coupled with her international reputation as an authority on Mary Magdalene, she enlarged her activities to lecturing and broadcasting, and became a formidable debater. Her interest in Mary Magdalene led to a thrice-staged sell-out play Holy Lies, Unholy Truth (once in St John’s Cathedral), as well as many important scholarly papers. Alison was even seen wearing a badge “Mary Magdalene for Pope” which she dared to wear to the Vatican pavilion at Queensland Expo 1988.

Although she left the Church many years ago and considers herself an agnostic rather than an atheist, she retains a passionate interest in Christianity, and continues to write and publish. Her main interest now is on Judas Iscariot, another misunderstood outsider, about whom she is working on another play.

Marian Free (1955 –)

Originator of Brisbane MOW, liturgist and priest

Click for More

Marian Free (1955 –)

A cradle Anglican, Marian Free was the joint co-ordinator of the Brisbane Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW). She was ordained priest in 1996 and was the first female priest to be elected to General Synod.

Marian Free was born in the UK but spent her first three and a half years in Nigeria before her parents moved to Brisbane. Apart from a year in Sydney and three in Christchurch, New Zealand, Marian has lived in Brisbane and surrounds ever since. A cradle Anglican, Marian was born into a Christian home to parents who became very much involved in their local church. Marian was to follow their example, becoming a member of Parish Council at 18. In the 1950’s and 60’s there was little liturgical scope for women. Only boys could be servers or sing in the choir. Thus, it was not until she was in her mid-20s that Marian saw a woman in the sanctuary. By this time Marian had a sense that she might be called to the ministry – but with whom could she share that? An opportunity arose in a Bible study group.

Fortunately, the idea was met with encouragement and Marian was urged to speak to her priest who, as a proponent of women’s ordination made an appointment for her to see the Archbishop. Archbishop Grindrod warned that it would be at least 8 years before the various Synods approved the legislation. Notwithstanding, he presented her with the book that she would have received had she been male. There followed not eight, but eleven years of waiting (and agitating) for the legislation to be passed.

In the interim, Marian began biblical studies which in turn became a PhD. At the same time she was fortunate to attend a retreat with Monica Furlong which became the launching pad for the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) in Brisbane. Marian became the joint co-ordinator with Gwen Roberts and held many roles in the group over a number of years including Public Relations and Liturgy. Usually with the help of others, Marian was privileged to create worship for our meetings and for our public gatherings. They tried to represent the feminine side of God and of our faith and used a variety of symbolic actions that spoke to our situation.

Marian’s interest in liturgy was further utilised during the Ecumenical Decade – Churches in Solidarity with Women, for which she was the Liturgical Co-ordinator.

Marian was ordained as a Deacon in 1994 (among the third group of women to be so ordained) and a Priest in 1996. By virtue of being among the earliest group and by virtue of her relative youth, Marian achieved a number of “firsts” for which she was recognised by a square in a Quilt in the Women’s Hall of Fame in Alice Springs. Marian was the first female priest to be appointed to the Western region and the first to be a Rector in that Region. Marian was the first female priest to be elected to General Synod and the first Residential Canon of St John’s Cathedral.

Patricia Brennan (1944-2011)

Founder of MOW, loving defier

Click for More

Patricia Brennan (1944-2011)

Patricia Brennan, founder of MOW in Australia, took her prophetic vocation seriously as an advocate for change in the Anglican Church. She turned being called ‘strident’ into ‘stir and tend’. She promoted ‘loving defiance’.

Patricia Brennan was a prophet of our times, medical doctor, forensic physician, missionary, wife, mother, grandmother, television presenter, poet, and sculptor. As founder of the National Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) in 1984, more than any other single individual, she put the ordination of women on the agenda of the Anglican Church and kept it in full view. From her death bed in Germany in 2010 she wrote, “In the absence of the founding witnesses the prophetic story will go down as an unfinished prophetic task, leaving it to the more detached historians to write yet another sanitised version of MOW”.

Patricia was born into a working class family and grew up in a friendly middle Anglican Church. She thought there were probably no radical thinkers in her church, but she said, “kneeling in the Choir I used to be having quite a few radical thoughts of my own when I was about 12”.

After graduation from medicine and internships, she became a missionary in Niger, Africa, at the edge of the Sahara where there were no doctors for hundreds of kilometres. She says, “I saw the tremendous suffering of women, they were about the same level as the beasts. She said, “Violence was only just emerging in my mind then as associated with gender and associated with religion”.

In 1982 Patricia was appointed to a Sydney Diocesan Committee to consider women’s ministry. She conducted a survey of theological students and women training for ministry, including questions about women’s ordination. This research project revealed deep dissatisfaction with the Anglican Church. When she submitted her findings to the Sydney committee they were disregarded.

In 1984, Patricia became the founder and President of the National Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW). She said, “The prophetic tradition has been one of bringing greater clarity to the purposes of God and it has both a negative and positive aspect: negative, because it rejects the dominant culture and exposes it as wrong; positive because it is radical, meaning it goes back to the root of the very intentions of God in revealing God’s purposes”.

At the formation of Sydney MOW, Patricia insisted that the word “ordination” be included in the name of the organisation. Some wanted to call it ‘Women in Ministry’. Well, she said, that’s like you want to be a doctor and you talk about women in health. If you call it women’s ordination you will name the problem.

Patricia had a great way with words and debate, particularly her ‘one-liners’ which the media loved. As her successor as President of National MOW, Dr Janet Scarfe, said, “her words were not empty spin, they were informed, insightful and devastatingly incisive”. She turned the word ‘strident’ which was often used of women in a derogatory sense into ‘stir and tend’. She stirred the ‘comfortably churched’ and tended to those who were distressed by their sometimes cruel treatment by the church. Another one of the sayings she used in MOW was ‘loving defiance’.

Women were ordained in the Anglican Church of Australia in 1992. Patricia was then back in Sydney where she had started 20 years ago. She said “This meant the end of my prophetic role…with what was locally not only a failed quest but patently hailed as a victory for true Christianity. I could no longer pew sit under the authority of the Jensens and Moore College. I went into existential mourning in the desert. Like Peter after the crucifixion, I took my concerns back to fishing. That is medicine, except that I chose to relive reform by becoming a forensic physician working in Emergency Departments and courts with abused patients especially women and children but without gender bias, sometimes with fierce opposition”.

Cecilie Lander (1948-)

MOW warrior, eventual priest

Click for More

Cecilie Lander (1948-)

Cecilie Lander is a MOW activist who transformed the heavy weight of generations of women who had been refused acceptance for Ordination to the threefold ministry of the Church of God.

“I didn’t mean to become an Anglican Priest.

I understand now how and perhaps why it happened.

It is perhaps harder to discern the underlying motivation. At the beginning of the journey, I was still struggling to ‘get God right’ so if anything, it was more about my own salvation than that of saving others’ souls.

By the mid 80’s, I had specialised in Neurology, had a flourishing Neurological practice and a Hospital appointment. Two sons aged 9 and 3 years kept my surgical husband and I busy. How could there be room for more.

On 25th August 1987, I posted my one and only ever letter to a newspaper. The Australian editor published it two days later. An avalanche of letters were published, phone calls followed resulting in community movements being established; the consequences continue to follow me.

The letter was written in response to Fr James Murray, Anglican Priest and Religious Writer for the Religion section of The Australian newspaper. He had opined his various reasons why women should not be ordained to the (Anglican) priesthood.

My letter was moderate in tone, logical, reasonable yet underpinned by pent up frustration, irritation, indignation, and a growing sense of gross injustice. The letter bore a single date, an ordinary day in an ordinary year but within its lines, it carried the heavy weight of generations of women who had been refused acceptance for Ordination to the threefold Ministry of the Church of God. Since I was a small girl, I had been heavily influenced by my mother who saw the injustice in women’s lives in so many areas and nowhere more obvious than the church in which we as family were involved.

The Movement for the Ordination of Women became an active group in Brisbane. While I was a founding member, my husband took more active participation than I could by virtue of the fact that I had two young children at home and was juggling a busy medical practice.

It took several years to begin to shift opinion and to get sufficient numbers to effect Synodical change. Brisbane Anglican Diocese has ordained women to the priesthood since 1992.

My own involvement with MOW and the Ordination of women was not ever about me being minister! My involvement (or so I thought!) was entirely to support women who believed that they had a calling to the priestly vocation.

However, simultaneously with this involvement, I was seriously struggling with the religious quest. I was fond of saying that, until I “got God right”, I could not be “up-front” in Church.

I sought theological clarity and struggled deeply with the ultimate question of ‘life and death’. The spade work of a Bachelor of Theology Degree allowed me to delve deeply into factual and reflective theology and philosophy. Two study trips to Israel/ Egypt and Syria/Turkey/ Greece allowed me physical immersion into biblical places.

However, it was the combination of meditation and Zen practice that shattered and re-created my spiritual world.

Then, one of the Anglican teachers asked me, “Cecilie, what are you going to do next?”

After much angst, a period of deep dis-ease and un-ease including a mountain top family retreat, I came down the mountain and called the Bishop.

“I think I have a calling to the priesthood…”

To this day, some Anglican Dioceses such as Sydney, not to mention the entire Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches refuse to ordain women to priestly ministry.

On a world scale, Islam has not begun to include women in leadership positions. Buddhism has softened towards women in some areas.

Cultural oppression of women is still prevalent and all too often it is disguised in religious garb.

The battle is far from over.”

Eileen Thomson Headmistress, priest and celebrator of the sacraments

Click for More

Eileen Thomson (1923-2010)

One of the first six women ordained priest, Eileen Thomson’s approach to her priestly ministry was through sacrament, Church, scholarship, history and tradition.

Eileen Thomson wrote in early 2000s, “The Rector (David Thomas) said, ‘Have you thought about ordination to the Diaconate?’ I replied, ‘certainly, but sadly that is for the next generation.’ He responded, ‘Don’t you be too sure.’”

She continued, “The lights really did flash around my head as my longing and various careers came together, followed by feeling calmly settled. The Rector wrote to the Master of Ordinands that night.”

The journey had been a long and winding road; indeed for much of Eileen’s life it was neither sealed nor more than a bush track. The beginnings were traditional; at Kambala and Meriden schools and St Anne’s Strathfield she was fascinated by the prayer book and Bible. Her mother and she referred often to ancestors in ministry including William Tindale and a Bishop Farrar, both martyred.

Eileen learned daily prayer from childhood; simple words thanking God for family, the Lord’s Prayer and reflection on scripture. She took very seriously the saying of the office.

With women barred from ordination, on leaving school in 1943 the way forward was the caring professions of education and social work. She completed a B.A. at Sydney University (remarkable for a woman in the 1940s in itself), a TH.L at the Australian College of Theology and further qualifications at Oxford and William Temple College/Cambridge as a Commonwealth student. In her words, “To change the world” she needed to be part of it. Energetic work in Britain and Australia led her to headmistress level.

She mused to an Archbishop in later years that as headmistress responsible for the life of the school, “one retired priest was needed just to celebrate the Friday Eucharist!”. A broad hint.

In 1962 she married stockman / economist Edgar Thomson. Soon, with four boys under five, faith assumed different dimensions. The road to faith was mostly stopping children crawling under pews at church to entertain the clergyman. Nevertheless her writings at the time demonstrate a strong continuing desire for leadership in preference to the stifling second fiddle life expected of 1970s housewives.

The catalyst for a quickening of the tempo was the sudden death of Edgar in 1976. She moved the family to his home town of Toowoomba for education and commenced as the Senior Social Worker at Baillie Henderson psychiatric hospital, a period she described “as nearest to ‘highways and hedges’”.

With the Church rediscovering and rebuilding the diaconate including embracing women, entering holy orders was a natural progression. With the roadway clear, recognised and understood by the Church hierarchy, Eileen became first a deacon in 1989 before being ordained priest in 1992.

Various roles followed; as Director building up Anglicare Western Region (1999-2004), serving on numerous Government boards, chaplaincy at University of Southern Queensland and working with diverse good groups. At a parish level there came the rota of parish life. Eileen was awarded the Archbishop’s Medal for her outstanding service in the Diocese.

In essence, eschewing noisy debate Eileen opted for a sacramental Church, scholarship, history and tradition linking. Whether in a church or anywhere else she believed clergy were there to give absolution, celebrate the Eucharist and deliver the message. This was Eileen absolutely!