The late 20th century – The Path to Ordination

There is no doubt that the women’s movement of the late 1960s had a role in emerging calls for an improved status for women in the church. The heart of the women’s ordination issue, however, was that exclusion from the priesthood did not accord with the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Angela Simmons (1939–)

Women’s advocate, pastoral carer, teacher and welfare worker

Click for More

Angela Simmons (1939–)

Angela Simmons studied theology at Moore College Sydney and Deaconess House from 1966 to 1968. She was awarded a scholarship for full time study with the NSW Department of Child and Social Welfare which became the springboard for employment with the Brisbane Anglican Diocese as Matron of the Church of England Women’s Shelter for unmarried expectant mothers.

Demand from young women (and older women) seeking residential care at that time was very high and referrals from within and outside of Queensland included some overseas countries. Ages ranged from 12 years of age to 39 years. Reasons for pregnancies were diverse and included rape, incest, failed abortions, ignorance, and a desire to be loved or to love.

Angela’s work did not go unnoticed. A writer in the Church Chronicle reported – “at the 1969 Brisbane Synod, attention was drawn to its Wednesday evening ‘Home Mission Hour’ when Miss Angela Simmons, Matron of the Women’s Shelter, Spring Hill, held Synod spellbound by her vivid, and at times disturbing account of the tragic problems with which she had to deal. Her insistence that for every problem of an unmarried mother there is also a problem of an unmarried father highlighted an aspect which many people never realise”. (Church Chronicle, 1st July 1969, Special Sessions, p.16)

A decision was made to swiftly and radically change the program at the Women’s Shelter from a medical focus to a family focused model. Blame and shame was no longer to be tolerated. Programs for the residents, their families and putative fathers were developed and attracted wide media attention in television, radio, newspapers and speaking engagements in churches and Synod throughout the Brisbane diocese.

The residence was given a colourful renovation and its drab grey walls and curtains replaced with cheerful homely features. Rooms were altered to provide for individual and group counselling, study for school students, craft and fun times. Space became available for visiting specialist personnel and film nights.

The process of allocating shame and blame had historically, its roots in the Post Reformation period when Henry VIII desperate for money, plundered the abbeys and churches as an income source. The abbeys had previously provided a safe haven for unmarried pregnant women and girls. This gave way to the financial burden of caring by the abbeys and churches to the introduced practice of shaming of these women (and men) by parading them before a congregation and exposing them to public condemnation and ridicule.

That attitude was still evident to some degree in 1969 when Angela discovered that some clergy visitors to the Women’s Shelter were placing pressure on residents by wanting to “hear their confessions” This was quickly dealt with and some clergy were banned from visiting.

A National seminar focusing on the Needs of Unmarried Mothers was one of the highlights of Angela’s time and enthusiastic support was given by many health professionals, legal identities, government organizations and church personnel.

In particular, government authorities had perplexing attitudes to adoption and screening and assessment of applicants to adopt was almost non-existent. Bluntly, supply ran ahead of demand and caused pain and suffering to surrendering mothers.

There was also some opposition from some critics who believed that lack of shaming and blaming would promote promiscuity. Angela recalled a tragic incident at the nearby Royal Women’s Hospital when a young woman requested to see her baby to say goodbye. The nurse cruelly said, “why would a thing like you want to see the baby” and at the same time grabbed the baby from the bassinet and flicked her finger on the baby’s chin which drew blood. This was the last time the young mother saw her baby. Fifty years later Angela is still overcome with sadness.

Visits by busloads of visiting parish groups for fundraising were halted as this was not providing confidentiality to the residents and was replaced by small groups of dedicated women who came to teach skills as well as making maternity clothes and baby layettes. Their contribution was outstanding. Many women from Queensland parishes sent parcels by mail and often sent “leaving and job seeking clothes”. Visits by other specialist personnel covered areas of options such as adoption, retaining custody, sex and health education, employment, and educational factors. There were unwelcome persons such as private detectives who trespassed on the grounds, complete with cameras. They were chased off and given the boot.

A recurring pattern was evident following speaking engagements in parishes or in media outlets. Without fail, Angela would be approached by emotional women (and sometimes men) to share their regret and sorrow in having been forced to surrender a baby for adoption. Some of these folk were in their 60s and 70s. No counselling, no adoption alternatives had been offered them.

Following her years at the Women’s Shelter Angela spent two years working in the Parish of St Stephen’s, Coorparoo with an old friend the Rev Harry Goodhew. His invaluable support and leadership opened a ministry in pastoral work, preaching, conducting services in nursing homes as well as inclusion in regional clergy meetings. Angela served as editor of the parish magazine and served on Diocesan committees researching women’s ministry and abortion.

Following two years as a teacher of Religious Studies at the Southport School she joined the staff of St John’s Upper Mt Gravatt working with the Reverend Dr Ray Barraclough which again proved to be a privilege and to enjoy the respect of being treated as an equal. Angela recalls a time when the Parish had to consider relinquishing her services because of financial difficulties. When Dr Barraclough heard of this, he volunteered to accept some of his salary in order to retain Angela. Astonishing.

The last 25 years of Angela’s working life included working with the Department of Family and Child Services in senior positions in Murgon, Maryborough, Woodridge, and Ipswich. Angela exercised an effective ministry which included troubled families.

Lorna Hallahan (1959-)

Organiser and defender of women and other excluded peoples.

Click for More

Lorna Hallahan (1959-)

Lorna Hallahan was an active parishioner in Anglican churches in Toowoomba and Brisbane. In the 1970s she was, with her sister, the first female altar server in Toowoomba. However, by the 1980s Lorna felt only anger at the systemic exclusion of women, gay and lesbian Christians, and disabled people in all parts of church life. As a social worker Lorna completed a PhD in disability theory and theology and rediscovered the power of incarnational theology within the Anglican tradition. She has returned to the Anglican Church.

‘The whole world is watching’ chanted a motley bunch of people sitting on Roma Street, Brisbane as the police moved in to arrest us. The 1982 Commonwealth Games in Queensland provided grounds for the Minister for Police to introduce strict anti-protest legislation. Concerned Christians, ecumenical Christians focussed on the rights of First Peoples, soon found ourselves inside the watch house. When I was released, my friend Rev Ray Barraclough took me to see the Anglican Archbishop, John Grindrod, to enjoin him to visit the protesters camped in nearby Musgrave Park. He poured me a whisky! Accompanying him days later amused me as people accosted him with fake confessions of sins of the flesh. Gentle but pointed mockeries, deeply embedded in a damaging history. A history of exclusion I also knew as a young woman of faith.

My sister and I were the first altar girls in our Toowoomba parish. In the mid-1970s male priests owned the sanctuary. When a new rector called us gormless for clunking around in our truly gorgeous platform sandals, my sister walked away. I was to take a different path. Accepted by University of Queensland Social Work, I launched my activist career through the Australian Student Christian Movement.

Of steadfast Anglicanism, I attended the parish where a friendly priest from my school, Peter Allan, was assistant. We went to St Mary’s Kangaroo Point in the middle of 1978. For the next five years we sought internal change in the Anglican Church. In Synod, Rev James Warner moved an ordination of women motion, which I seconded. Along with Rev Ray Barraclough we also moved motions on Aboriginal Affairs, poverty, peace and nuclear disarmament. I attended the initial weekend retreats for the Movement for the Ordination of Women. The youngest in the group, I cherished the faithful support of women who had long endured the stabs and slights of the patriarchal church. The highlight was organising a public meeting to support the Sex Discrimination Bill (1984). Another Christian group, Women who Want to be Women, threatened to disrupt our meeting, so we, feminists and our male allies, met in the parish church, predicting correctly that they would not intrude.

The last time I served at the altar was 16 May 1976. The following day my leg was amputated as step one in a long journey to cure an aggressive bone cancer. Just over two years later, when my friends were under arrest at another Concerned Christians rally, I met David Bulloch – now my partner of over forty years and father of our two sons. In 1985, after completing a project on the Church and Social Justice, being an organiser for ASCM and for the Campaign Against Nuclear Power, I stepped away from church life for nearly a decade. From early adolescence, the Eucharist had offered joyful connection. By then, I felt only anger at the systemic exclusion denying women, gay and lesbian Christians and disabled people full and equal participation in all parts of church life. This decision brought a certain freedom; but also, a real loss. A loss only partly addressed even now as the Church struggles to fully include all God’s children.

Monica Furlong (1930-2003)

Moderator of English MOW, catalyst for Brisbane MOW

Click for More

Monica Furlong (1930-2003)

Monica Furlong was an English author, journalist, writer and activist. She was the Moderator of the English Movement for the Ordination of Women.

Monica was invited by the Sydney Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) to visit Australia for six weeks in 1984. Their hope was to build a national organisation of MOW. So Monica visited five Australian major cities, to mobilise people interested in the ordination of women and to help the thinking/action process along.

She noted the differences between the Australian scene and England. The major difference was geographical, making ‘togetherness’ a problem. Another difference was that the women’s movement in English society had made more impact on the Anglican Church than in Australia where it was just beginning. A further difference was that the major opposition came from Evangelicals who saw the obstacle entirely as one of ‘headship’, mainly from Sydney.

The obstacles to ordination in Australia seemed formidable. In a number of parts of the Australian church there were no deaconesses, nor any facilities for training women.

This first meeting of Brisbane women was held at the Augustinian Priory, Clayfield in April 1984 with Monica as their guest. She described the tired Anglican Church as a “croquet lawn” with the women’s movement “like a great spring of water gushing up in the middle of the lawn”.

Women came together, a disparate group, from different backgrounds and churchmanship, mostly active in their Parishes. They shared their call to ordained ministry, talked a lot, wept and raged. Joan Lethlean said “…under Monica’s quiet leadership great healing took place that weekend”. Many of the women present went on to make significant contributions to the movement, such as Mavis Rose, Gwenneth Roberts, Marian Free and Philippa Wetherell.

Monica was also in Sydney, Canberra, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth. She was strongly attacked by a clergyman/journalist in the secular press. Women who met Monica were inspired with fresh enthusiasm and determination to work more actively and visibly for the ordination of women.

Monica sensed that MOW in England was valued by the Australian women as a model, and a source of encouragement. She found herself wondering what might be achieved by Anglican women supporting one another worldwide, and how much stronger we might be if we were seen publicly united.

The Circle of Sisters (1997–2007)

Working for reconciliation

L to R: Gwenneth Roberts, Alex Gater, Diane Press

Click for More

The Circle of Sisters (1997–2007)

In 1997, racism in the church was creatively responded to through the formation of the Circle of Sisters. The group emerged out of the Lay and Ordained Women’s Conference in Brisbane. The Circle became a place for reconciliation.

A memorable and significant event that was born out of the Lay and Ordained Women’s conference in Brisbane in 1997, and which became a continuing source of communication with Aboriginal women, and a force for reconciliation, was the Circle of Sisters.

Diane Prass speaks of this life changing experience initiated by meeting Alex Gater. “I was deeply involved with its formation and I marvel now at how it happened. I went to the Conference having no idea what to expect and knowing almost no one. I recall the naming of thirteen barriers between women and women, women and society, and women and the church. Thirteen large boxes were appropriately labelled and filled with our concerns written on slips of paper. I noticed Alex standing alone beside the box marked Racism, and I thought I should join her. Soon there were six of us, totally absorbed in discussion of the nature of racism in society and in the church, and of the barriers to reconciliation. Alex and her sister Lesley made racism real for us as they spoke of hurtful experiences. The terms “black and white” were seen to divide our nation. I realised that although I believed in reconciliation, I had actually grown up in Australia not knowing any Aboriginal people. I had seen them in parks and read about them in newspapers but I did not know them personally, and I thought how can I be reconciled to people I do not know or understand? Others in the group felt the same.

I had lived many years in PNG and shared their joy at independence, but when I returned to Australia I realised sadly that the languages, culture, land, and identity that they had been able to retain in PNG had been tragically lost for our Aboriginal people.

Our group felt so strongly moved that we made our first steps towards reconciliation right then and there, deciding to form a support group linking each other in friendship and sisterhood, working at grass roots level in our parishes and communities to reach out to our Aboriginal sisters.

The prayer of Reconciliation from our Prayer Book was read. Then I put forward our resolve to form this circle which would keep us in touch long after the conference, and offer hospitality, support and friendship to each other, and especially to our Aboriginal sisters in their struggle for reconciliation and justice. There were over sixty of us and the interest and enthusiasm was overwhelming. Alex spoke about how we could break down the barriers of racism in our everyday lives – educate ourselves, read, find out the truth, stand up for the truth when we heard lies, and write letters of support.

Since then, Parish activities (I was President of Enoggera Mothers’ Union), newsletters and home gatherings were our main ways of keeping the circle alive and hearing the Aboriginal viewpoint. So I look back now and remember, and marvel at the birth of the Circle of Sisters, thinking how the Holy Spirit worked in us in surprising and wonderful ways”.

The Circle disbanded in 2007. Some moved on from their positions in the Church, some left the Church. It remained for individual people to support their Aboriginal sisters.

Heather Toon (1937-)

First woman ordained in Brisbane

Click for More

Heather Toon (1937-)

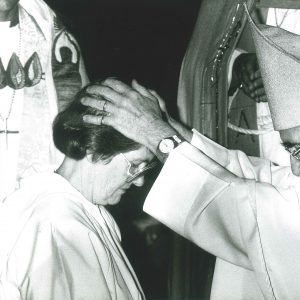

Heather Toon was the first woman to be ordained in the Diocese of Brisbane. She was ordained deacon in 1988. She is Archdeacon Emeritus in the diocese. She was a leader in the training of those called to the diaconate.

Archdeacon Emeritus Heather Toon was the first woman to be ordained in the Anglican Diocese of Brisbane.

Heather began her training for the Diaconate after attending a Pastoral Care Conference in Hawaii with Bishop George Hearn in the early 1980’s. Whilst there, Heather met deacons from other countries and learned what diaconal ministry really meant. She had believed for some time that she had been called by God to a ministry, but before Hawaii, wasn’t quite sure what that ministry was. Hawaii was a real “Aha!” moment for Heather.

When Heather returned to Rockhampton, she began training for the Diaconate under the guidance of Bishop George Hearn, although at that time, the Anglican Church of Australia had not approved the ordination of women. In 1986, when she had almost completed her training, and Rockhampton Diocese was debating whether to ordain women or not, Heather’s husband Bernie, was transferred with his work to Brisbane.

On their arrival in Brisbane, Heather and Bernie began to worship at St Clement’s on the Hill, Stafford, where their friend and former priest, the Rev’d Godfrey Fryar was parish priest. Stoically, Heather continued training at St Francis’ College under the guidance of Archbishop John Grindrod, in the hope that soon, the Brisbane Synod would consent to ordaining women.

Finally, on The Feast of the Annunciation, 25th of March, 1988 Heather was ordained as a Deacon in the Church of God to serve in the Parish of St Clement’s, Stafford. The Archbishop had given Heather the choice as to whether she wanted to be ordained in the Cathedral or in her home parish of Stafford, and Heather chose Stafford. It was a great celebration and women from around the diocese were jubilant that at last, they may have the opportunity to be ordained too.

The next few years were not easy for Heather as there was quite an amount of resistance to the ordination of women in the Church generally, and in Brisbane diocese in particular. However, Heather went about her ministry quietly and lovingly.

Heather was licensed to Stafford and for the next twenty years worked in an honorary capacity assisting at services and taking pastoral care of many parishioners. She was also heavily involved in the Diocese, working to prepare programs at St Francis College for the training of deacons, encouraging and interviewing enquirers to the Diaconate and preparing in-service training days for those men and women who had been ordained deacons. She led quiet days for the diocese and was appointed to several committees including committees of the National Church.

In 1996, Archbishop Hollingworth collated Heather as Archdeacon of the Household of Deacons involving Heather even more in Diocesan activities. She retired from this position in 2002. During this time, Heather was President of the Australian Anglican Diaconal Association for several years. This association meets somewhere in Australia every two years for a conference and of course, Heather was instrumental in many a planning program.

Heather travelled widely, attending two North American Deacons Association conferences in 1997 and 1999 and World Conferences for Diakonia in Germany and England as well as leading the planning and organising of the World Conference held here in 2001 when 500 delegates from 39 countries attended.

The church in this Diocese owes much gratitude to Heather for her quiet and determined love for Christ, his Church and those who are called to serve. She was a real “boundary rider’, quietly breaking barriers in her gentle and caring way and showing the way for women in this diocese to serve their Lord.

The Movement for the Ordination of Women

A landmark social change

One of the most successful advocacy efforts on behalf of women in the 20th century was the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) through the 1980s and 1990s. Its aim of the priesting of women was achieved in 1992. Since then women have gone on to become bishops and archbishops. However, the struggle is not over in some dioceses, notably Sydney.

Click for More

The early years – England comes to Australia

Maude Royden, suffragist and first proponent of women’s ordination in the Church of England visited Australia in 1928, including a trip to Brisbane. Here she was welcomed by prominent dignitaries, including staying at the Governor’s residence. She preached at Albert St Methodist Church but was not welcomed by the local Church of England.

Brisbane MOW is born, 1984

A long gap ensued before Brisbane women banded together to advocate for women’s ordination in the Anglican Church of Australia. Unlike Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide Dioceses, there was no prior activist group of women focussing on women’s priesting in Brisbane. The first meeting of Brisbane women was initiated by Gwenneth Roberts who had met with Dr Patricia Brennan, founder of the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) in Sydney. Gwenneth was greatly inspired by Patricia Brennan to initiate MOW Brisbane with Marian Free.

This first meeting of Brisbane MOW was held at the Augustinian Priory, Clayfield in April 1984. The guest presenter was Monica Furlong, Moderator of English MOW, who described the tired Anglican Church as a “croquet lawn” with the women’s movement “like a great spring of water gushing up in the middle of the lawn”. Women came together, a disparate group, from different backgrounds and churchmanship, mostly active in their Parishes. They shared their call to ordained ministry, talked a lot, wept and raged. Joan Lethlean said “…under Monica’s quiet leadership great healing took place that weekend”. Many of the women present went on to make significant contributions to the movement, such as Mavis Rose, Gwenneth Roberts [link], Marian Free and Philippa Wetherell.

Although not an official body of the Anglican Church, MOW Brisbane was officially launched on October 6, 1984 at St Francis’ Theological College; Principal Canon James Warner was a great supporter of women’s ordination. Supportive men such as Mervyn Lander, John Roberts, Kevin Lethlean and others were members of the group. Women from other denominations – Catholic, Uniting Church, Lutheran and others – became members.

The work of MOW

The task of MOW was focussed – to persuade members of the local Brisbane Synod and the General (National) Synod to pass legislation to enable women to be deacons, priests and bishops. It pursued its campaign with vigorous advocacy – Synod members speaking to motions for women’s ordination, communicating with Bishops and Clergy who supported women’s ordination, protest banners displayed outside Cathedral and Churches, letters to the Editor of local and national Anglican newspapers, representation at MOW National meetings, attendance at National Conferences, and a presence at General Synods in Sydney.

The 1992 conference

A landmark National MOW Conference was held at Halse Lodge, Noosa, combined with a women’s Art Exhibition, in 1992. Dame Quentin Bryce, then Federal Sex Discrimination Commissioner, opened the Exhibition. She wept as she noted the failure of the recent General Synod to pass enabling legislation for women priests by one vote in the House of Clergy.

Opposition

MOW experienced some strong opposition in Brisbane with the formation of the Campaign for the Historical Male Priesthood (CHAMP). MOW was task oriented, expending much of its energies in conflict. Their lack of pastoral care resulted at times in internal disagreements on strategies, and moments of despair, part of the price of the struggle. Internally, members wrote liturgies and prayers, studied feminist theology, had fun engaging in performances of creative satire, and sang inclusive language hymns.

MOW disbands

MOW Brisbane disbanded in 1997, following the ordination of women as Deacons in 1988 and Priests in 1992. At an evening of reunion and celebration the high and low spots were remembered; but they had all been enriched by their experiences and strong friendships forged as they challenged the Anglican Church to respond to the world wide movement of the Spirit that allowed women to follow their calling.

In the words of Patricia Brennan, “We few, we happy few, we band of sisters (and the odd brother) we will remember while others forget, that we gave everything we had to give, once in our lives, for justice!”

MOWatch forms

A few years after many setbacks and achievements culminated in the ordination of women to the priesthood MOW was described as ‘one of Australia’s most forceful reform movements.’

Women campaigning for priesthood and for visible participation in the church’s life, liturgy and leadership was as much a novelty in the Diocese of Brisbane as elsewhere. Some diocesan leaders were supportive – to varying degrees – while others condemned MOW as no more than secular feminists who had turned their attention to the church.

Click here to View the MOW Page

Contains Biographies and videos of many of the key advocates

The First Priests – 1992

Pioneers of the faith

There were six in the first group of women ordained priest in the Diocese of Brisbane in 1992.

Photo Credit: Michael Stephenson

Click for More

Joan Pascoe (1939–2019)

Joan Pascoe, one of the first women ordained priest in Brisbane in 1992, was a teacher and missionary in Brisbane and Papua New Guinea.

Leah Mary Shaw (1923–2010)

Leah Shaw was one of the first women priests in the Diocese. She was a teacher, finally at Toowong High School where she was Deputy Principal. After she retired in 1983 she joined St George’s church in Mt Tamborine where she became a Lay Assistant. She was ordained priest in 1992, shortly before her 70th birthday.

Kaye Pitman (1936 –)

At the age of 56, Kaye Pitman was one of the six women ordained priest in 1992, the first time it was possible in Brisbane. She was a teacher, student, MOW member and the director of the deacon and priestly formation programs in Brisbane.

Val Graydon (1947 – )

Val Graydon is one of the first group of six women who were ordained priest in the diocese in 1992. She reflects on the significance of MOW in the ordination journey. Val is currently national president of MOWatch, a daughter organisation of MOW which works for the ordination of women in all dioceses.

Pat King (1933–2012)

Among the first women ordained priest in the diocese, Pat King was a gentle, compassionate woman who did not shy away from breaking boundaries. Pat was able to break through traditions that constrained women’s roles.

Eileen Thompson (1923-2010)

Eileen Thomson believed in a sacramental church combining scholarship, history and tradition. As one of the first six priests in the diocese she believed clergy were there to give absolution, celebrate the Eucharist and deliver the message.

Click here to View the First Six Page

Contains Biographies of those ordained in 1992

MOWatch – Into the Future…

In 1995 National MOW hosted a conference in Sydney for ordained women. Titled Astonishing Women the principal speaker was Bishop Penny Jamieson from New Zealand.

Click for More

In 1995 National MOW hosted a conference in Sydney for ordained women. Titled Astonishing Women the principal speaker was Bishop Penny Jamieson from New Zealand. Seventy-five women clergy from Australia attended; it was an amazing time and particularly enjoyable when long-standing lay members of MOW joined us for a very entertaining evening of celebration. Bishop Penny congratulated the organizers but stated strongly that a conference for women clergy only, must never happen again – the work of the movement was an effort of lay and ordained together. Her words were taken seriously. When the next conference was hosted by women from the Diocese of Brisbane in 1997, Gwenneth Roberts, a lay woman from MOW Brisbane and myself shared in the planning of the conference Visionary Women.

This was a time of adjustment for National MOW and branches. The long hard road for the ordination of women enabled a breakthrough, but the task would not be over until all dioceses in Australia accepted women to be ordained. Later that year, the National body revised the way forward and a new constitution was accepted. MOW became MOWatch; the name was the suggestion of Alison Gent a dedicated member from Adelaide who considered this to reflect the ongoing work of MOW and the need to ‘watch’ what was happing for ordained women. The struggle continues, particularly in the diocese of Sydney where the determination to overcome the refusal to accept women as priest or bishop is maintained.

From 1997 there was a lot of work to do and residential conferences held every two years was a wise decision. MOWatch also decided to invite different dioceses to host the occasion. This enabled local people to plan and provide for attendees to experience various perspectives of women’s ministry across the country. After Brisbane, host dioceses included Adelaide, Alice Springs (diocese of the Northern Territory), Perth and Kincumber in (diocese of Newcastle). Individual branches also held various conferences, including the celebration of significant milestones in many areas of ministry.

With the help of generous donations, we were also able to invite overseas speakers to these conferences. Many visiting for the first time; Jane Shaw, and Paula Gooder each came on two occasions, Esther Mombo from Kenya, Jenny Plane Te Paa from New Zealand and Kay Goldsworthy who was to be consecrated bishop (and Archbishop) in Australia. Perhaps the most exciting outcome of these events, was the opportunity to hear from Australian women travelling alongside MOWatch, in particular those writing books from various perspectives of the Church.

The dedication of our Movement to continue the aim for every diocese to admit women to the three-fold order remains strong. From the new Anglican year book for Australia we will soon provide the present statistics for women clergy across the country on our website. There is also a page related to MOW in the year book and a photo that is a ‘first’ for this publication. Do take a look and follow us on Facebook.

In the process of updating our Constitution, we have changed MOWatch back to MOW, but kept our domain as http://mowatch.com.au As we remember the past we look to the future as we plan to celebrate 30 years of the ordination of women to the priesthood in Australia in 2022.

Val Graydon